What do we know about the pipe network and how it works? Answer: not everything. But over the last decade we have certainly increased our understanding of how it works. We know that the pipe under the landfill takes water from the springs, overland water from the hills and stormwater from the road. The water is contaminated by leachate from the tip, but we don’t know if that is intentionally or only through cracks in the ageing pipe structure.

The following are three parts of the system that have posed much head scratching and thought for quite some time, although the last (possibly) shows a welcome development.

Piping the Creek

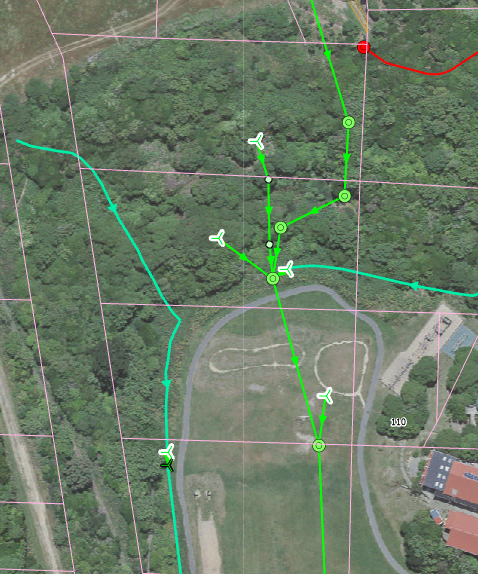

When they first started the landfill, they had to put the small creek they were covering into a pipe. The largest nearby spring was also directed into the pipe, the other springs must have been deemed not sufficiently large to bother with. And that is the interesting point: as you work up the valley putting the water in the pipe, the quantity of water gradually gets smaller, because that is what streams do. So at what point do you stop the pipe, because if you go too far the water can’t get in! Looking at the maps there is a point just above the school where the main pipes stop, and a stormwater pipe enters from the side.

What too are the little propellor shapes, are they vents? (No surface evidence of that.) Are they there to let spring water in or leachate? Maybe one day someone might have the answer for us.

The Jumping Weir

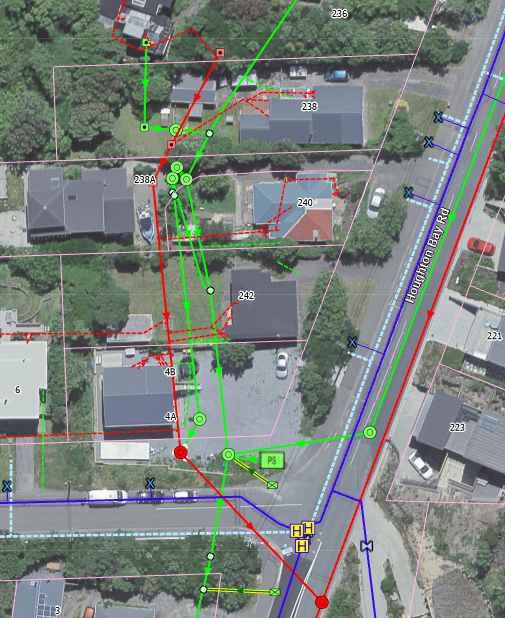

The jumping weir is a system designed to divert leachate from the landfill into the sewer during low water flow, but to allow it to overflow into the stormwater system (and hence onto the beach) during heavy rainfall events (anything over 30 mm). The jumping weir consists of the three green close together manhole lids shown in the photo.

Given the increasing number of heavy rainfall events now, this means that the frequency of contaminated water entering the marine reserve is much higher. But the system has never worked completely effectively.